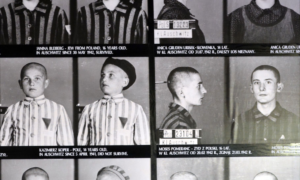

David Herman reviewed the photographic exhibition “Seeing Auschwitz” here last week. I too have been to the show at 81 Brompton Road in South Kensington, London. It was a powerful experience.

The mood in the room was sombre and few people talked, so intent was their concentration onthe images which were, to say the least, disturbing. The quiet background piano music was slow, deep and chilling.

I went to Auschwitz and Birkenau a number of years ago. Auschwitz is a former Polish Garrison, a row of orderly brick buildings. Birkenau, however, felt like a wasteland, which made the end of the railway track seem even more bleak on that cold and misty November afternoon.

The camp at Auschwitz is a huge tourist attraction and it seemed ironic that we were all queuing up and being herded into the camp. We saw mounds of hair, pictures of abandoned suitcases and piles of shoes. At one point we stood in one of the gas chambers, except that I had misunderstood and didn’t actually realise it was one, which was perhaps just as well. My emotions were strangely blocked – I didn’t feel overwhelmed, which surprised me. It was probably due to an element of self-protection, but I found my lack of reaction disturbing.

But Birkenau was another matter. This was partly down to our guide, who relayed the horrors foisted upon the inmates by Josef Mengele, known as the “Angel of Death”, the SS officer and physician who performed deadly experiments on prisoners in the “interests” of genetic research. He was particularly focused on experimenting with twins.

Our Polish guide was a woman in her sixties and she was intense. As she described the horrific medical experiments in graphic detail, her eyes bored into ours, as if to say: “Are you concentrating, really concentrating?”

Afterwards, I asked her how long she’d been a guide at the camp. “Thirty years,” she told me. “In that time I have taken three groups a day, six days a week.” She told me that many survivors had returned with their children, perhaps in an attempt to lay the ghost, but also to pass on knowledge of the horrors to the next generation in the hope that such a thing wouldn’t be repeated.

Small things struck me at the exhibition. The woman in the wheelchair, cradling her small son on her lap as he listened to the commentary on the headphones. He can’t have been more than about six years old. My reaction was that he was surely too young to be faced with such images. It didn’t seem fair on him.

Few people looked at one another. We were too lost in our own thoughts or, more probably, we felt unable to meet one another’s eyes. Apart from shock, there seemed to be a general feeling of shame in the room.

The other thing that hit me was the collective silence. I wondered how many had been personally affected by the camps – probably quite a number. And yet, in all the hush and the haunting music, there seemed to be an air of sheer human decency among us. We made sure not to block one another’s view of the photographs, voices were kept to a minimum. We respected one another’s experience. How could one behave selfishly or boorishly when faced with all this?

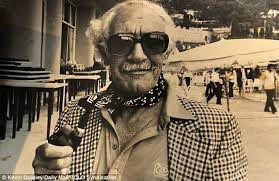

And then I saw a photo of one of the death marches and I was reminded of my old friend and tennis journalist, Laurie Pignon, who was subjected to one of those marches. Laurie was kind, hugely flamboyant, great fun, always positive and much loved by the players. “I never said anything unkind about them,” he told me.

The All England Club recognised this and he was proud to have been made an honorary member of the club, the only journalist to have been so.

But beneath all the bonhomie, Laurie had his demons, which frequently emerged when under the influence of too much alcohol.

He’d start talking about that winter death march. Laurie had been a POW, spending five years in forced labour. “We walked along the cliff paths behind the people in striped pyjamas. When one of them fainted from exhaustion, a German officer would just kick them over the ridge.” Laurie was subjected to a mock execution, just for the amusement of those officers. “I stood up straight and saluted as they pulled the trigger. I didn’t want them to think I was a coward.”

Laurie teamed up with two other men. He told me that the way they coped with the ordeal was to pretend they were on a walking holiday. “We’d say ‘what a lovely view. Aren’t we lucky. We really must come back.’” The three men survived and remained close friends. They lived long lives, with Laurie dying aged 93 in 2012.

I was also reminded of my time in the 1970s in Israel on a kibbutz, many of whose members comprised camp survivors. Some still bore tattoos on their arms. All seemed totally traumatised. They lived on Valium. One day, some volunteer painted a swastika on a wall, just for a laugh.

But back to the exhibition. The message, of course, is that of “Lest We Forget” — except that, in the final section, we are offered images and explanations of subsequent genocides: the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the Tutsi in Rwanda, Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica, Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, Yazidi in Northern Iraq and other horrors perpetrated by ISIS.

Finally, and most chillingly, we meet with the present day and are presented with the resurgence of anti-Semitism, in the form of swastikas spray-painted on Jewish tombstones. Perhaps the final message is, in fact, a question: have we really learned from those concentration camp atrocities?